| Type | Private |

|---|---|

| Industry | Computer software |

| Founded | 1985; 36 years ago |

| Founder | |

| Headquarters | Abingdon, England |

Key people | |

| Products | Security software |

| Services | Computer security |

| Revenue | $640.7 million (2018)[1] |

| US$46.9 million (2018)[1] | |

| US$66.3 million (2018)[1] | |

| Owner | Thoma Bravo |

Number of employees | 3,319 (2018)[1] |

| Website | sophos.com |

Sophos Artificial Intelligence was formed in 2017 to produce breakthrough technologies in data science and machine learning for information security. We're currently focused on machine learning, large scale scientific computing architecture, human-AI interaction, and information visualization. Sean Gallagher is a Senior Threat Researcher at Sophos. Previously, Gallagher was IT and National Security Editor at Ars Technica, where he focused on information security and digital privacy issues, cybercrime, cyber espionage and cyber warfare. He has been a security researc.

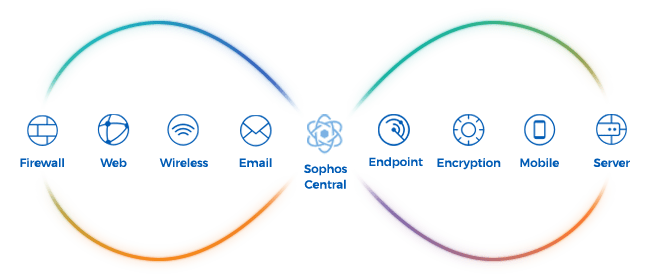

Sophos Group plc is a British security software and hardware company. Sophos develops products for communication endpoint, encryption, network security, email security, mobile security and unified threat management. Sophos is primarily focused on providing security software to 100- to 5,000-seat organizations. While not a primary focus, Sophos also protects home users, through free and paid antivirus solutions (Sophos Home/Home Premium) intended to demonstrate product functionality. It was listed on the London Stock Exchange until it was acquired by Thoma Bravo in February 2020.

History[edit]

Sophos was founded by Jan Hruska and Peter Lammer and began producing its first antivirus and encryption products in 1985.[2] During the late 1980s and into the 1990s, Sophos primarily developed and sold a range of security technologies in the UK, including encryption tools available for most users (private or business). In the late 1990s, Sophos concentrated its efforts on the development and sale of antivirus technology, and embarked on a program of international expansion.[3]

In 2003, Sophos acquired ActiveState, a North American software company that developed anti-spam software. At that time viruses were being spread primarily through email spam and this allowed Sophos to produce a combined anti-spam and antivirus solution.[4] In 2006, Peter Gyenes and Steve Munford were named chairman and CEO of Sophos, respectively. Jan Hruska and Peter Lammer remain as members of the board of directors.[5] In 2010, the majority interest of Sophos was sold to Apax.[6] In 2010, Nick Bray, formerly Group CFO at Micro Focus International, was named CFO of Sophos.[7]

In 2011, Utimaco Safeware AG (acquired by Sophos in 2008–9) were accused of supplying data monitoring and tracking software to partners that have sold to governments such as Syria: Sophos issued a statement of apology and confirmed that they had suspended their relationship with the partners in question and launched an investigation.[8][9] In 2012, Kris Hagerman, formerly CEO at Corel Corporation, was named CEO of Sophos and joined the company's board. Former CEO Steve Munford became non-executive chairman of the board.[10] In February 2014, Sophos announced that it had acquired Cyberoam Technologies, a provider of network security products.[11] In June 2015, Sophos announced plans to raise $US100 million on the London Stock Exchange.[12] Sophos was floated on the FTSE in September 2015.[13]

On 14 October 2019 Sophos announced that Thoma Bravo, a US-based private equity firm, made an offer to acquire Sophos for US$7.40 per share, representing an enterprise value of approximately $3.9 billion. The board of directors of Sophos stated their intention to unanimously recommend the offer to the company's shareholders.[14] On 2 March 2020 Sophos announced the completion of the acquisition.[15]

Acquisitions and partnerships[edit]

From September 2003 to February 2006, Sophos served as the parent company of ActiveState, a developer of programming tools for dynamic programming languages: in February 2006, ActiveState became an independent company when it was sold to Vancouver-based venture capitalist firm Pender Financial.[16] In 2007, Sophos acquired ENDFORCE, a company based in Ohio, United States, which developed and sold security policy compliance and Network Access Control (NAC) software.[17][18] In November 2016, Sophos acquired Barricade, a pioneering start-up with a powerful behavior-based analytics engine built on machine learning techniques,[19] to strengthen synchronized security capabilities and next-generation network and endpoint protection. In February 2017, Sophos acquired Invincea, a software company that provides malware threat detection, prevention, and pre-breach forensic intelligence.[20][21][22]

In March 2020, Thoma Bravo acquired Sophos for $3.9 billion.[23]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ abcd'Annual Report 2018'(PDF). Sophos. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ^'Sophos: the early years'. Naked Security.

- ^'Exterminator Tools'. Windows IT Pro. 15 November 1999. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^'Sophos acquires anti-spam specialist ActiveState'. www.sophos.com. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- ^'Sophos Management Team | Global Leaders in IT Security'. sophos.com.

- ^'Apax Partners to acquire majority stake in Sophos'.

- ^'Board of Directors'.

- ^'The Bureau Investigates article'. Archived from the original on 4 December 2011.

- ^'Statement from Sophos on Recent Media Reports'.

- ^'Sophos Board of Directors webpage'.

- ^'Sophos Acquires Cyberoam to Boost Layered Defense Portfolio'. Infosecurity Magazine.

- ^'Sophos Plans $100 Million London IPO'.

- ^'Sophos joins the UK's top public companies in the FTSE 250'.

- ^'Sophos founders exit before Thoma Bravo sale'. Global Capital. 5 December 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^'Sophos opens new chapter with take-private acquisition'.

- ^'ActiveState Acquired by Employees and Pender Financial Group; Company Renews Focus on Tools and Solutions for Dynamic Languages'. Business Wire. 22 February 2006. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^'Sophos buys Endforce for network access control'. Network World. 11 January 2007. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^Wauters, Robin. 'Sophos beefs up on online security, acquires Dutch security software firm SurfRight for $31.8 million'. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ^https://www.sophos.com/en-us/press-office/press-releases/2016/11/sophos-acquires-security-analytics-start-up-in-ireland.aspx

- ^'Sophos Adds Advanced Machine Learning to Its Next-Generation Endpoint Protection Portfolio with Acquisition of Invincea'. Sophos. 8 February 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^'Sophos grows anti-malware ensemble with Invincea'. Sophos. 8 February 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

One may ask, if you already have great next-generation technology, why do you need Invincea’s technology?...Think of Invincea as the superhero that takes our ensemble to the next level – the entity that adds neural network-based machine learning to the team.

- ^'Sophos to Acquire Invincea to Add Industry Leading Machine Learning to its Next Generation Endpoint Protection Portfolio'. Invincea. 8 February 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^'Thoma Bravo completes $3.9B Sophos acquisition'. TechCrunch. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

External links[edit]

Transport Layer Security has been one of the greatest contributors to the privacy and security of Internet communications over the past decade. The TLS cryptographic protocol is used to secure an ever-increasing portion of the Internet’s web, messaging and application data traffic. The secure HTTP (HTTPS) web protocol, StartTLS email protocol, Tor anonymizing network, and virtual private networks such as those based on the OpenVPN protocol all leverage TLS to encrypt and encapsulate their contents—protecting them from being observed or modified in transit.

Over the past decade, and particularly in the wake of revelations about mass Internet surveillance, the use of TLS has grown to cover a majority of Internet communications. According to browser data from Google, the use of HTTPS has grown from just over 40 percent of all web page visits in 2014 to 98 percent in March of 2021.

It should come as no surprise, then, that malware operators have also been adopting TLS for essentially the same reasons: to prevent defenders from detecting and stopping deployment of malware and theft of data. We’ve seen dramatic growth over the past year in malware using TLS to conceal its communications. In 2020, 23 percent of malware we detected communicating with a remote system over the Internet were using TLS; today, it is nearly 46 percent.

There’s also a significant fraction of TLS communications that use an Internet Protocol port other than 443—such as malware using a Tor or SOCKS proxy over a non-standard port number. We queried against certificate transparency logs with the host names associated with malware Internet communications on ports other than 443, 80, and 8080, and found that 49 percent of the hosts had TLS certificates associated with them that were issued by a Certificate Authority (CA). A small fraction of the others manually checked used self-signed certificates.

But a large portion of the growth in overall TLS use by malware can be linked in part to the increased use of legitimate web and cloud services protected by TLS—such as Discord, Pastebin, Github and Google’s cloud services—as repositories for malware components, as destinations for stolen data, and even to send commands to botnets and other malware. It is also linked to the increased use of Tor and other TLS-based network proxies to encapsulate malicious communications between malware and the actors deploying them.

Google’s cloud services were the destination for nine percent of malware TLS requests, with India’s BSNL close behind. During the month of March 2021, we saw a rise in the use of Cloudflare-hosted malware—largely because of a spike in the use of Discord’s content delivery network, which is based on Cloudflare, which by itself accounted for 4 percent of the detected TLS malware that month. We reported over 9,700 malware related links to Discord; many were Discord-specific, targeting the theft of user credentials, while others were delivery packages for other information stealers and trojans.

In aggregate, nearly half of all malware TLS communications went to servers in the United States and India.

We’ve seen an increase in the use of TLS use in ransomware attacks over the past year, especially in manually-deployed ransomware—in part because of attackers’ use of modular offensive tools that leverage HTTPS. But the vast majority of what we detect day-to-day in malicious TLS traffic is from initial-compromise malware: loaders, droppers and document-based installers reaching back to secured web pages to retrieve their installation packages.

To gain insight into how usage of TLS in malware has changed, we took a deep dive into our detection telemetry to both measure how much TLS is used by malware, identify the most common malware that leverage TLS, and how those malware make use of TLS-encrypted communications. Based on our detection telemetry, we found that while TLS still makes up an average of just over two percent of the overall traffic Sophos classifies as “malware callhome” over a three-month period, 56 percent of the unique C2 servers (identified by DNS host names) that communicated with malware used HTTPS and TLS. And of that, nearly a quarter is with infrastructure residing in Google’s cloud environment.

Surprise packages

Malware communications typically fall into three categories: downloading additional malware, exfiltration of stolen data, and retrieval or sending of instructions to trigger specific functions (command and control). All these types of communications can take advantage of TLS encryption to evade detection by defenders. But the majority of TLS traffic we found tied to malware was of the first kind: droppers, loaders and other malware downloading additional malware to the system they infected, using TLS to evade basic payload inspection.

It doesn’t take much sophistication to leverage TLS in a malware dropper, because TLS-enabled infrastructure to deliver malware or code snippets is freely available. Frequently, droppers and loaders use legitimate websites and cloud services with built-in TLS support to further disguise the traffic. For example, this traffic from a Bladabindi RAT dropper shows it attempting to retrieve its payload from a Pastebin page. (The page no longer exists.)

We’ve seen numerous cases of malware behaving this way in our research. The PowerShell-based dropper for LockBit ransomware was observed retrieving additional script from a Google Docs spreadsheet via TLS, as well as from another website. And a dropper for AgentTesla (discussed later in this report) also has been observed accessing Pastebin over TLS to retrieve chunks of code. While Google and Pastebin often quickly shut down malware-hosting documents and sites on its platform, many of these C2 sources are abandoned after a single spam campaign, and the attackers simply create new ones for their next attack.

Sometimes malware uses multiple services this way in a single attack. For example, one of the numerous malware droppers we found in Discord’s content delivery network dropped another stage also hosted on Discord, which in turn attempted to load an executable directly from GitHub. (The GitHub code had already been removed as malicious; we disclosed the initial stages of the malware attack to Discord, along with numerous other malware, who removed them.)

Sophos Security For Desktop Computer

Malware download traffic actually makes up the majority of the TLS-based C2 traffic we observed. In February 2021, for instance, droppers made up over 90 percent of the TLS C2 traffic—a figure that closely matches the static C2 detection telemetry data associated with similar malware month-to-month from January through March of 2021.

Covert channels

Malware operators can use TLS to obfuscate command and control traffic. By sending HTTPS requests or connecting over a TLS-based proxy service, the malware can create a reverse shell, allowing commands to be passed to the malware, or for the malware to retrieve blocks of script or required keys needed for specific functions. Command and control servers can be a remote dedicated web server, or they can be based on one or more documents in legitimate cloud services. For example, the Lampion Portuguese banking trojan used a Google Docs text document as the source for a key required to unlock some of its code—and deleting the document acted as a kill-switch. By leveraging Google Docs, the actors behind Lampion were able to conceal controlling communications to the malware and evade reputation-based detection by using a trusted host.

The same sort of connection can be used by malware to exfiltrate sensitive information—transmitting user credentials, passwords, cookies, and other collected data back to the malware’s operator. To conceal data theft , malware can encapsulate it in a TLS-based HTTPS POST, or export it via a TLS connection to a cloud service API, such as Telegram or Discord “bot” APIs.

SystemBC

One example of how attackers use TLS maliciously is SystemBC, a multifaceted malicious communications tool used in a number of recent ransomware attacks. The first samples of SystemBC, spotted over a year ago, acted primarily as a network proxy, creating what amounted to a virtual private network connection for attackers based on SOCKS5 remote proxy connection encrypted with TLS—providing concealed communications for other malware. But the malware has continued to evolve, and more recent samples of SystemBC are more full-featured remote access trojans (RATs) that provide a persistent backdoor for attackers once deployed. The most recent version of SystemBC can issue Windows commands, as well as deliver and run scripts, malicious executables, and dynamic link libraries (DLLs)—in addition to its role as a network proxy.

SystemBC is not entirely stealthy, however. There’s a lot of non-TLS, non-Tor traffic generated by SystemBC—symptomatic of the incremental addition of features seen in many long-lived malware. The sample we recently analyzed has a TCP “heartbeat” that connects over port 49630 to a host hard-coded into the SystemBC RAT itself.

The first TLS connection is an HTTPS request to a proxy for IPify, an API that can be used to obtain the public IP address of the infected system. But this request is sent not on port 443, the standard HTTPS port—instead, it’s sent on port 49271. This non-standard port usage is the beginning of a pattern.

SystemBC then attempts to obtain data about the current Tor network consensus, connecting to hard-coded IP addresses with an HTTP GET request, but via ports 49272 and 49273. SystemBC uses the connections to download information about the current Tor network configuration.

Next, SystemBC establishes a TLS connection to a Tor gateway picked from the Tor network data. Again, it uses another non-standard port: 49274. And it builds the Tor circuit to the destination of its Tor tunnel using directory data collected via port 49275 via another HTTP request. There, the progression of sequential ports ends, and in the sample we analyzed it tries to fetch another malware executable via an open HTTP request over the standard port.

The file retrieved by this sample, henos.exe, is another backdoor that connects over TLS on the standard port (443) to a website that returns links to Telegram channels—a sign that the actor behind this SystemBC instance is evolving tactics. SystemBC is likely to continue to evolve as well, as its developers address the mixed use of HTTP and TLS and the somewhat predictable non-standard ports that allow SystemBC to be easily fingerprinted.

AgentTesla

Like SystemBC, AgentTesla—an information stealer that can also function in some cases as a RAT—has evolved over its long history. Active for more than seven years, AgentTesla has recently been updated with an option to use the Tor anonymizing network to conceal traffic with TLS.

We’ve also seen TLS used in one of AgentTesla’s most recent downloaders, as the developers have used legitimate web services to store chunks of malware encoded in base64 format on Pastebin and a lookalike service called Hastebin. The first stage downloader further tries to evade detection by patching Windows’ Anti-Malware Software Interface (AMSI) to prevent in-memory scanning of the downloaded code chunks as they’re joined and decoded.

The Tor addition to AgentTesla itself can be used to conceal communications over HTTP. There is also another optional C2 protocols in AgentTesla that that could be TLS protected—the Telegram Bot API, which uses an HTTPS server for receiving messages. However, the AgentTesla developer didn’t implement HTTPS communications in the malware (at least for now)—it fails to execute a TLS handshake. Telegram accepts unencrypted HTTP messages sent to its bot API.

Dridex

Dridex is yet another long-lived malware family that has seen substantial recent evolution. Primarily a banking Trojan, Dridex was first spotted in 2011, but it has evolved substantially. It can load new functionality through downloaded modules, in a fashion similar to the Trickbot Trojan. Dridex modules may be downloaded together in an initial compromise of the affected system, or retrieved later by the main loader module. Each module is responsible for performing specific functions: stealing credentials, exfiltrating browser cookie data or security certificates, logging keystrokes, or taking screenshots.

Dridex’s loader has been updated to conceal communications, encapsulating them with TLS. It uses HTTPS on port 443 both to download additional modules from and exfiltrate collected data to the C2 server. Exfiltrated data can additionally be encrypted with RC4 to further conceal and secure it. Dridex also has a resilient infrastructure of command and control (C2) servers, allowing installed malware to fail over to a backup if its original C2 server goes down.

These updates have made Dridex a continuing threat, and Dridex loaders are among the most common families of malware detected using TLS—overshadowed only by the next group of threats in our TLS rogues’ gallery: off-the-shelf “offensive security” tools repurposed by cybercriminals.

Sophos Security Blog

Metasploit and Cobalt Strike

Offensive security tools have long been used by malicious actors as well as security professionals. These commercial and open-source tools, including the modular Cobalt Strike and Metasploit toolkits, were built for penetration testing and “red team” security evaluations—but they’ve been embraced by ransomware groups for their flexibility.

Over the last year, we’ve seen a surge in the use of tools derived from offensive security platforms in manually-deployed ransomware attacks, used by attackers to execute scripts, gather information about other systems on the network, extract additional credentials, and spread ransomware and other malware.

Sophos Free Download

Taken together, Cobalt Strike beacons and Metasploit “Meterpreter” derivatives made up over 1 percent of all detected malware using TLS—a significant number in comparison to other major malware families.

And all the rest

Potentially unwanted applications (PUAs), particularly on the macOS platform, also leverage TLS, often through browser extensions that connect surreptitiously to C2 servers to exfiltrate information and inject content into other web pages. We’ve seen the Bundlore use TLS to conceal malicious scripts and inject advertisements and other content into web pages, undetected. Overall, we found over 89 percent of macOS threats with C2 communications used TLS to call home or retrieve additional harmful code.

There are many other privacy and security threats lurking in TLS traffic beyond malware and PUAs. Phishing campaigns increasingly rely on websites with TLS certificates—either registered to a deceptive domain name or provided by a cloud service provider. Google Forms phishing attacks may seem easy to spot, but users trained to “look for the lock” alongside web addresses in their browser may casually type in their personally identifying data and credentials.

Traffic analysis

All of this adds up to a more than 100 percent increase in TLS-based malware communications since 2020. And that’s a conservative estimate, as it’s based solely on what we could identify through telemetry analysis and host data.

Sophos Security Vm

As we’ve noted, some use TLS over non-standard IP ports, making a completely accurate assessment of TLS usage impossible without deeper packet analysis of their communications. So the statistics sited in this report do not reflect the full range of TLS-based malicious communications—and organizations should not rely on the port numbers related to communications alone to identify potential malicious traffic. TLS can be implemented over any assignable IP port, and after the initial handshake it looks like any other TCP application traffic.

Even so, the most concerning trend we’ve noted is the use of commercial cloud and web services as part of malware deployment, command and control. Malware authors’ abuse of legitimate communication platforms gives them the benefit of encrypted communications provided by Google Docs, Discord, Telegram, Pastebin and others—and, in some cases, they also benefit from the “safe” reputation of those platforms.

We also see the use of off-the-shelf offensive security tools and other ready-made tools and application programming interfaces that make using TLS-based communications more accessible continuing to grow. The same services and technologies that have made obtaining TLS certificates and configuring HTTPS websites vastly simpler for small organizations and individuals have also made it easier for malicious actors to blend in with legitimate Internet traffic, and have dramatically reduced the work needed to frequently shift or replicate C2 infrastructure.

All of these factors make defending against malware attacks that much more difficult. Without a defense in depth, organizations may be increasingly less likely to detect threats on the wire before they have been deployed by attackers.

SophosLabs would like to acknowledge Suriya Natarajan, Anand Aijan, Michael Wood, Sivagnanam Gn, Markel Picado and Andrew Brandt for their contributions to this report.